Your menstrual cycle hormones explained

In this article

What's the lowdown?

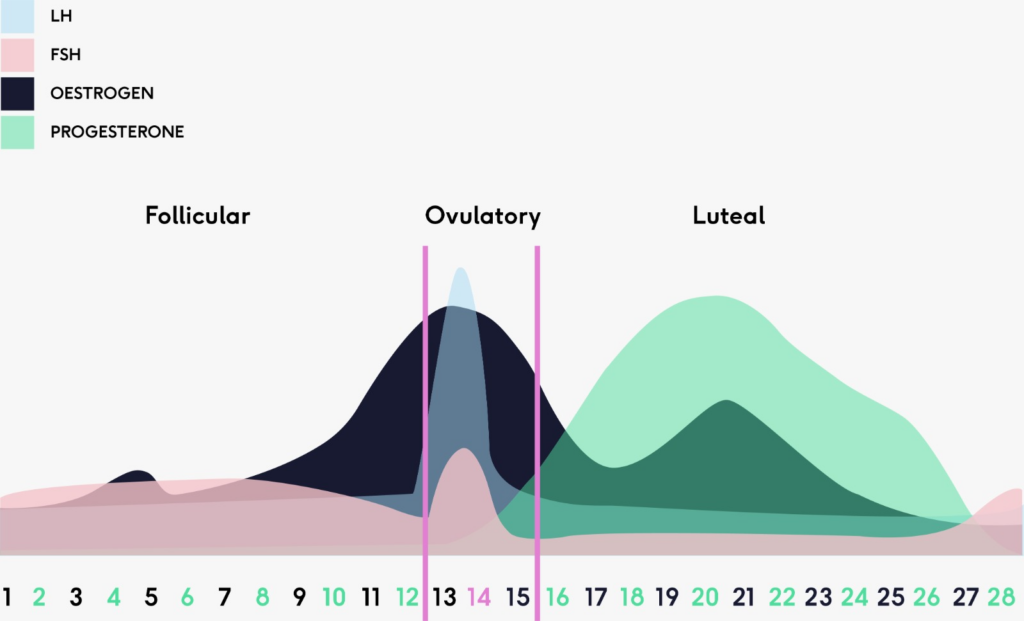

There are 4 main period hormones that run our menstrual cycle: oestrogen, progesterone, luteinising hormone and follicle stimulating hormone

The menstrual cycle can be separated into the follicular phase and luteal phase

The follicular phase occurs before ovulation and the luteal phase after ovulation

Ovulation occurs around the middle of your cycle, when an egg is released from the dominant follicle

Just a few years ago, talking openly about the menstrual cycle was seen as taboo. Now, it’s at the centre of scientific and political debate, and about time too.

No matter when you went to school, this new world of menstrual awareness takes some navigating, and may include some concepts that you haven’t come across before.

Here, we’ll go over how menstrual cycle hormones interact in a menstruating woman who isn’t on any kind of hormonal contraception, and how these interactions change throughout her cycle.

What are hormones?

- Hormones are chemicals that direct parts of your body to behave in certain ways.

- Hormones relating to your cycle and fertility are known as ‘sex hormones’, and these include ones you might have heard of, such as oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone, as well as other less-well-known hormones, such as Follicle Stimulating Hormone and Lutenising Hormone.

- Each of these hormones is created in different places around the body, including the glands, the ovaries and the uterus, and some may act as a signal to other parts of the body to start creating a different hormone in order to control a process.

Your menstrual cycle explained

While period trackers have proved invaluable to many women in recent years, ovulation tracking is only just starting to gain popularity, and not only among women who are trying to conceive; understanding our ovulation patterns can actually give us insight into the rest of our cycle.

Though this process is clearly a cycle, it also has two distinct parts: the phase before ovulation when the uterus is gearing up to ovulate and prepare the lining for a fertilised egg, and the phase after ovulation when the uterus maintains its lining for any fertilised eggs to implant in.

Before ovulation:

Menstrual phase

The time of the month I dread, not sure if you do too! This is the time when the endometrial lining in your womb is shed through the cervix and vagina. Most periods last around 5-7 days and occur every 28-30 days. Some people might have heavy or light periods and even irregular cycles.

- Hormones: Progesterone and oestrogen are typically at its lowest level during this phase, triggering the uterine lining to shed.

Follicular phase

The follicular phase takes place before ovulation, and the start is signalled by the beginning of a period up until ovulation. This phase lasts about 10-20 days but can vary between people.

In women, oestrogen is mainly produced in the ovaries, though its production is controlled by the release of other hormones made in the pituitary gland. Estradiol is the main oestrogen responsible for the menstrual cycle, and its levels increase during the first ten days. When estradiol is detected in the lining of the uterus (aka endometrium), the lining is stimulated to grow and thicken.

- Hormones: Both progesterone and oestrogen are low at the start of this phase, and increase as it progresses.

Follicular development

A follicle is a tiny bag of fluid within your ovary. Each follicle contains just one egg, which it stores until it’s mature.

In the 10-20 days before ovulation, Follicular Stimulating Hormone, produced in the pituitary gland (a bean-shaped gland in the base of the brain) has an X-Factor moment and selects only the most advanced follicle to proceed to ovulation3. This chosen follicle sets off a hormonal chain reaction that results in ovulation (unfortunately not a contract with Simon Cowell and a nationwide tour).

Follicular Stimulating Hormone is kept in check by progesterone and oestrogen, and when these two hormones fall during menstruation, it takes its chance and rises, stimulating the most advanced follicle in the ovary to mature4. When the follicle reaches a certain size, it starts to release large amounts of an oestrogen called estradiol, which triggers a ‘Luteinising Hormone surge’, which occurs 34-36 hours before ovulation.

Luteinising Hormone is also made in the pituitary gland, and it is this hormone that signals to the follicle to release the egg, resulting in ovulation. Luteinising Hormone then signals to the remains of the follicle, now an empty structure known as the ‘Corpus Luteum’, to release progesterone.

Ovulatory phase

About halfway through your menstrual cycle, between day 13-15, the egg is released from the dominant follicle. During ovulation, the follicle breaks open and releases the mature egg into the fallopian tube. A new follicle needs around 120 days to reach maturity, but while many follicles begin this process, usually just one makes it to full maturity and ovulation2.

This egg stays alive for 12-24 hours, and if it doesn’t get fertilised by sperm, it is simply flushed out of the body. We generally ovulate in the middle of our cycle, though this varies between individuals1.

- Hormones: Oestrogen is produced by the dominant follicle and the levels increase as the follicle grows. When oestrogen is high enough, the brain triggers a large surge in luteinising hormone which stimulates the release of the eggs. Right after ovulation has taken place, oestrogen levels take a sharp drop.

After ovulation:

Luteal phase

After ovulation, progesterone released by the Corpus Luteum (dominant follicle that once held the egg) works on reducing estradiol, stopping the growth and thickening of the lining of the uterus. Progesterone, however, maintains the thickness of the lining, and its levels remain high until the Corpus Luteum starts to disintegrate.

If the egg is not fertilised, and it does not implant in the lining of the uterus, then the Corpus Luteum breaks down from day 9 after ovulation5. This means that levels of progesterone fall, leading to the breakdown of the uterine lining, which – you guessed it – leaves the body as a period.

At the end of the luteal phase, the lining of the uterus starts to break down, causing a period to start, and this wonderful cycle begins all over again.

- Hormones: Progesterone is the predominant hormone in this phase. If the egg is not fertilised, the levels rise and drop quickly which is responsible for premenstrual symptoms. Both the drop in progesterone and oestrogen leads to menstruation.

Historically, scientific and medical research has failed to include women in its studies, creating a gap in the knowledge of how our menstrual cycles affect our health and wellbeing. Slowly (but surely!) a change is occurring thanks to campaigners and scientists flagging the importance of women’s involvement in research, and the collection of data about menstruation.

Your cycle can affect more than you think: your energy, mood, sleep, immune system, skin, hair and so much more. It is a great indicator about your overall general health and any changes could suggest health problems or reproductive issues. Do not neglect your menstrual health, listen to what your body is trying to tell you.

Our medical review process

This article has been medically reviewed for factual and up to date information by a Lowdown doctor.