Everything you need to know about vulval cancer

In this article

What's the lowdown?

Vulval cancer is pretty rare — only about 1,400 cases a year in the UK — and it’s mostly seen in post-menopausal women. But hey, no matter your age, it’s always smart to get familiar with your vulva and keep an eye out for any changes. Knowledge is power, right?(1)

69% of vulval cancer cases are preventable.(1)

The best prevention is knowing what your vulva looks like so you can spot any changes early.

There are 9 symptoms of vulval cancer.(2)

The HPV vaccine, which is free from your GP until age 25, can help protect you.

What is vulval cancer?

Cancer is a scary thing and difficult to think about, let alone talk about, but it’s important to know the risks, signs and symptoms so it can be prevented and treated early for the best outcome.

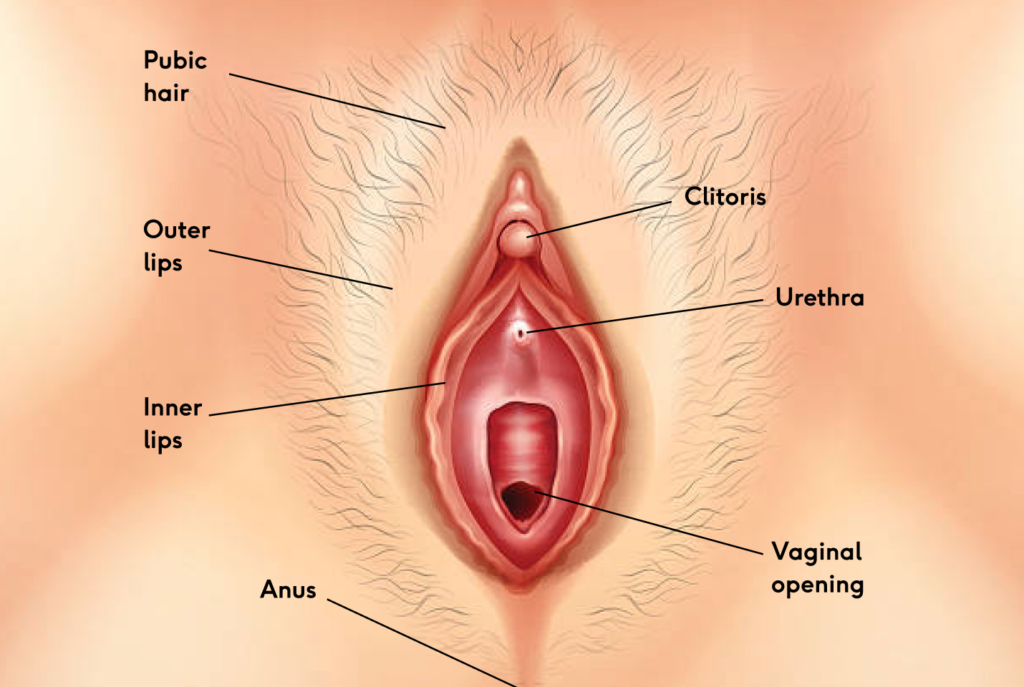

Vulval cancer, or vulvar cancer, affects the vulva — that’s the external part of the genitals, not the vagina (a common mix-up, but they’re different!). The vulva includes all the bits on the outside, like the labia, clitoris, and the soft area around the vaginal opening.

The vulva includes: the mons pubis where pubic hair often grows, the labia majora or outer labia (the larger lips), the labia minora or inner labia (the smaller lips, which are often a bit stretchy) and the clitoris (or clit, the bundle of nerves above the vaginal opening covered by a hood, the pleasure centre).Vulval cancer is rare,1 thankfully, but can affect any part of the vulva including the parts mentioned above. It can also affect the Bartholin’s glands.3 These two little glands, rarely seen as they’re so small, sit either side of the vagina and secrete fluid to help lubricate the vagina.

Types and stages

There are several types of vulval cancer.

· The most common is vulval squamous cell carcinoma which causes about 90 out of 100 cases of vulval cancer. This type often starts in the labia but is also possible in the clitoris and Bartolin’s glands, although much rarer.4

· The next most common is vulval melanoma. This one is less than 10 cases in 100 cases of vulval cancer. Melanomas are often linked to sun exposure and skin cancer. Sure, your vulva doesn’t get a lot of sun, but melanomas can still show up there because those cells are all over your body! The most common locations for this cancer are the labia and clitoris.4 As with skin melanomas, White people are more likely to develop vulval melanomas than Black people.5

· Other types include: Paget’s disease of the vulva (often associated with other cancers elsewhere in the body 6), verrucous carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, sarcoma and Bartholin’s gland carcinoma.4

Stages of vulval cancer are how doctors describe the cancer including how far it has progressed. Each vulval cancer will have a stage and a type. There is also a condition called vulval intraepithelial neoplasia or VIN for short.

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Before cancer develops there may be signs of cell changes called precancerous changes. In the vulva these changes are called vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN).7 You may have heard of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or CIN before when attending your cervical screening, VIN is similar but in the vulva rather than the cervix. It’s a similar situation though!

VIN isn’t cancer but could become cancer. The risk is there but it doesn’t mean that it definitely will progress into a cancer, having VIN doesn’t mean you’ll develop vulval cancer. VIN is graded based on how the cells look, it is either low grade (few cell changes) or high grade (more cell changes).

Image from Cancer Research UK 7

Signs and symptoms of vulval cancer

Think of it like a body MOT — just like you might check your breasts, getting to know your vulva is just as important. Don’t shy away from a mirror; the more you know your bits, the quicker you’ll spot anything that’s off. And if something doesn’t look or feel right, don’t just shrug it off — your health is worth that extra check.

Vulval cancer can look like:2

· A lump or swelling on your vulva

· Pain and soreness

· A mole on your vulva that changes shape or colour

· Lasting itch

· Visible open sore or growth

· Thickened or raised patches of lighter or darker skin

· Burning pain when you wee

· Unexplained bleeding from your vulva

Symptoms can sometimes mimic less serious conditions like thrush or urinary tract infections (UTIs, where bacteria enter your urethra and bladder). But it’s always best to get checked by a GP if you’re ever in doubt.

Causes and risk factors

There’s no one thing that causes vulval cancer, but some factors can increase your risk. Getting older is one of them (yep, the same goes for many cancers). Other factors include:

· Human papillomavirus (HPV). High risk HPV types are suspected to cause about 70% of vulval cancer cases. As with cervical cancer, it is only persistent infections that are associated with VIN and vulval cancer.8 The HPV vaccine helps to protect against these infections and is available free from your GP up until the age of 25 if you haven’t already had it.

· Weakened immune system. If you’ve had an organ transplant or have HIV there’s an increased risk you could pick up infections like HPV leading to an increased risk of vulval cancer

· Lichen sclerosus is an auto-immune condition generally found in post-menopausal women which can lead to VIN that could become vulval cancer.

· VIN. Abnormal vulva cell changes that could become vulval cancer.

· Having had cervical cancer or abnormal cells in the cervix. This risk factor is again linked back to HPV being the culprit of both cervical and vulval cancer.

· Smoking. This increases the risk of developing VIN and vulval cancer as it weakens the immune system and could lead to a higher chance of HPV infection.

Preparing for your first doctor’s appointment

If you notice something that’s off, don’t hesitate — book that doctor’s appointment. You know your body better than anyone, so trust your gut.

Never worry about wasting the doctor’s time or that your problem isn’t important. That little twinge of a worry often sticks around until you make that appointment and get some answers. It’s totally normal to feel nervous about these things. If it helps, bring a friend or a family member along for support. Your health is always worth it.

Before your appointment perhaps write some notes on exactly what changes you’ve noticed so you won’t forget anything when you see the doctor. Jot down when you noticed the changes, what the changes are, if the changes come and go and if anything makes the changes better or worse.

It’s also good to note down any other key health information such as: the date of the 1st day of your last period (if applicable), any family history of cancer, any current medications (if your doctor doesn’t already have a record) and even if you take any supplements.

The doctor will usually examine your vulva and may also do an internal examination. You can ask for a chaperone during the examination.

For an internal examination it will be similar to a cervical screening examination, if you’ve had one of those before. Make sure your bottom is right at the end of the examination bed—it saves the awkward shuffle down when the doctor pulls back the curtain!

This examination might feel a bit uncomfortable, but remember — you’re in control. If anything hurts or doesn’t feel right, you can ask to stop whenever you need. It’s completely okay to pause, take a moment, or ask questions at any time — your comfort is the priority.

Getting a diagnosis (what happens?)

Once the examination is done, your GP will go over what they found. If anything looks concerning, they might refer you to a specialist for further checks. This is often a two week wait urgent referral meaning you’ll be seen within two weeks of the referral being made by your GP.9

At the specialist centre they will perform the same examination as your GP, they may also scan you using an ultrasound machine and may also take a biopsy (a small sample of the affected tissue). Blood tests may also be carried out to check your overall health. You may also attend a colposcopy appointment. At a colposcopy a doctor uses a microscope called a colposcope to take a closer look at your cervix. They may also perform a vulvoscopy with the colposcope, allowing the doctor to look closely at your vulva for any changes that aren’t visible to the naked eye.10

If a biopsy is taken, it goes to the lab where a scientist examines it under a microscope, takes pictures and notes their findings. A consultant doctor will review these to determine if the tissue is cancerous and label the cancer with a stage using a staging system from the biopsy along with any scans taken (like MRI or CT scans). If VIN is found, it will be graded on how abnormal the cells look. Your specialist will contact you with the diagnosis and next steps, which might include surgery to remove the affected skin, followed by further treatment to ensure all cancer is removed.

It’s the most normal thing in the world to be scared, worried or anxious about all these appointments and examinations. Cancer is scary, fact. Vulval cancer is rare and that can make it even harder to talk about with family and friends. There are others in the same situation though and charities with hotlines if you ever need to talk to someone about what you’re going through such as Eve Appeal Ask Eve service, GO Girls, Cancer Research CancerChat and Macmillan Cancer support.

Staging and grading

Vulval cancer is staged using a system from the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).11 This system helps doctors decide how to treat the cancer.

Cancer grows bigger and can invade or spread to other nearby areas. It can also metastasise (spread) to other, more distant areas via the bloodstream or the lymphatic system and lymph nodes.

Lymph nodes are clumps of cells that often get bigger or swollen when you get ill with an infection or if cancer is present. The groin area, near the vulva, contains lots of lymph nodes. These lymph nodes may be removed to check if cancer cells are in them. Think of your lymph nodes like checkpoints; they’re the first place cancer might stop by, so doctors check them closely.Below is table showing the basic staging of vulval cancer and what it means:12

| Stage | Description |

| Stage 1 (I) | Tumour only within the vulva. |

| Stage 2 (II) | Tumour in vulva and also nearby areas such as the vagina, urethra (the tube urine passes through) or anus. No cancer cells in the lymph nodes. |

| Stage 3 (III) | Tumour in vulva and also nearby areas such as the vagina, urethra or anus. Cancer cells found in the lymph nodes and/or in more of the nearby areas such as vagina, urethra, bladder or rectum. |

| Stage 4 (IV) | Cancer has fixed to the bone or metastasised beyond the pelvis area and found at distant locations |

Survival rates

The survival rate for vulval cancer is 57.9% meaning almost 6 in 10 women diagnosed with vulval cancer survive over ten years. The survival rate is higher in those aged 15-44 with almost 9 in 10 women surviving over ten years. The 75-99 vulvar cancer age group have a survival rate of almost 5 in 10 women who have been diagnosed with vulval cancer.1

It’s important to note that vulval cancer is more common in older women who are post-menopausal, and mostly occurs in those over 90 years old.1 This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t get to know your vulva though, the earlier you start, the better!

Treatment options

Vulval cancer treatments usually start with surgery to remove the affected area. It might sound daunting, but your doctor will be there every step of the way, making sure you understand all your options.

Surgery could involve a small excision, where just the cancer and a little bit of healthy tissue around it (called a margin) are removed to catch any stray cancer cells. In some cases, though, more extensive surgery might be needed, like removing larger parts or even the entire vulva, in a procedure called a vulvectomy. The extent of surgery depends on how advanced the cancer is.

And if reconstruction is something you’re interested in, be sure to chat with your doctor to see what’s possible. Remember, the plan is always tailored to what’s best for you.

After surgery the doctor may suggest radiotherapy (high energy waves used to kill any remaining cancer cells) and/or chemotherapy (a drug that targets fast dividing cells, like cancer cells). You may also have chemotherapy before your surgery if the doctor thinks it would help in your case. These treatments can cause side effects so it’s best to ask your doctor about them and if there’s any way to make them easier to handle.

Treatment is very personalised and truly depends on the stage of the cancer. These are just some of the options available, but your doctor may know of clinical trials where new drugs are being tested that you could be eligible for.13,14

After treatment is complete, what happens?

After your treatment is complete, you’ll be followed up on a regular basis. How often depends on how you’re doing after treatment, your cancer stage and any other vulva skin conditions you may also have, such as VIN. Your doctor will determine the best timings for your situation. You’ll usually be followed up for about 3 years though15.

Each follow up will involve examination by a doctor or nurse and may also involve tests. The doctor or nurse will check on your wellbeing, mentally and physically. Tell them anything that’s troubling you regarding your health post-treatment including any side effects or symptoms from treatment. They will also inform you of any signs to look out for that may indicate the cancer coming back.15

Anxiety about cancer returning is common and normal. You should be given resources by your doctor about who you can contact between follow up appointments including a specialist nurse and charities focusing on cancer care such as Macmillan Cancer support.

Surgery and the removal of part of your genitals can have a profound mental impact on you. Your body changing so suddenly is bound to have an effect. It may lead to women feeling less feminine, or like you’ve lost a part of your identity. This could have an impact on intimate relationships and sex may be more difficult physically due to the surgery. It could also make you less up for sex and potentially worry about what your partner will think.

These issues can cause a feeling of isolation, like no one else knows what you’re going through. If you feel this way, voice these feelings to your treatment team and, if you can, open up to close friends and family. They all only want what’s best for you and for you to feel well, in all senses. Support groups for cancer survivors exist and can be a safe space to talk about how you’re feeling and what you’re going through as well. Life after surviving cancer is possible. It takes time, support and love so please don’t be afraid to reach out to those closest to you if you’re anxious or worried.

Our medical review process

This article has been medically reviewed for factual and up to date information by a Lowdown doctor.