The Lowdown on HPV: Your questions answered

In this article

What's the lowdown?

HPV is nothing to be ashamed of.

HPV is a common virus, basically like a cold. 80% of us will have it at some point in our lives. Anyone can get it.

There are many different types of HPV known as ‘strains’; some types are known to cause abnormal cells in the cervix, which can over time lead to cervical cancer, while other types can cause warts.

HPV can be passed on through any sexual contact (with the genital area), and is therefore sometimes unhelpfully referred to as a sexually transmitted infection (STI). However, it is not the same as STIs like chlamydia or gonorrhoea.

HPV is impossible to fully prevent and can be passed on even during protected sex with a condom.

The HPV virus can lie dormant in your system for years, so if you’re in a monogamous relationship it doesn’t mean someone has cheated – either of you could have caught it beforehand and it’s almost impossible to tell from who and when this might have happened.

What is HPV?

HPV stands for human papillomavirus. Itis a common virus that can affect the cervix, lining of the mouth and throat, the vagina, vulva and anus. There are over 200 known types of HPV, and the jab offered in schools protects against a few of these. HPV is categorised into two main types – low-risk and high-risk. Most types of HPV are low-risk, may not cause any symptoms, or appear as warts on your hands, feet or genitals.

High-risk HPV is linked to some cancers, which is why it is tested for in cervical screening in the UK.

How do you get HPV?

The HPV virus is passed on by skin to skin contact. This includes through touch, oral contact and sex, and condoms may not completely prevent the spread. However, it is NOT a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

HPV virus symptoms

Usually, the HPV virus has no symptoms at all! SOme people may develop warts on their hands or genital warts, depending on the type of HPV. HPV infection of the cervix may not cause any symptoms. If you develop bleeding after sex or abnormal bleeding, you should see your doctor.

Does HPV go away?

Even if your results do show high-risk HPV, it can go away by itself. Your body will usually work to get rid of it and it will clear up on its own without any issues. Most people are HPV negative in 2 years, and you probably wouldn’t have even known you had it if you hadn’t gone for a screening.

If HPV is so common, why do we have screening for it?

99% of cervical cancers are caused by persistent infection of high-risk HPV, hence why it’s the first thing they screen for. It takes years for high-risk HPV to cause cervical cancer.

Cervical screening tests aren’t a test FOR cancer, they’re simply an efficient way to ensure that any high-risk HPV is monitored and any abnormal cell changes that may develop into cancer over many years are caught and treated early. While most people will have HPV at some point in their life, keeping an eye on your cervix with regular screening helps to ensure cells don’t get the chance to develop into cervical cancer.

If your screening results come back every time as HPV positive, this also doesn’t necessarily mean you will develop cervical cancer. If you are HPV positive but have a normal smear, you’ll be invited for another screen in 12 months time. If you are HPV positive and have low or high grade dyskaryosis on the smear, you will be invited for a colposcopy.

Does it impact men / do I need to tell my partner?

A review of thirteen studies explored women’s concerns about telling a sexual partner they have tested positive for HPV. This is called disclosure. The study showed concerns fitted into three main categories:

- the anticipated psychological impact of disclosure and fears of rejection

- if disclosure was even really necessary

- how to manage disclosure.

When it comes to sex, as HPV isn’t like other STIs – which we can test for and treat – it’s not necessary to tell your partner if you have it. However you may want to discuss your HPV result with your partner. It’s important to remember that condoms don’t necessarily prevent you from getting HPV as the virus is passed on through skin to skin contact with the genitals. So, if you bring it up – make sure you can give them the facts: 80% of us will get it, they probably have it or have had it already without knowing, and the only way you can avoid it is by avoiding sex altogether for the rest of your life.

Can you get HPV again if it’s gone away?

There is still more research needed about HPV reinfection between couples. The current evidence suggests that it is hard to develop a response to the virus that would protect against reinfection. This means that there is a possibility that reinfection between couples could happen. HPV may also stay in the body but be dormant – meaning it is not picked up on a test. It can then become active again – meaning a test will then show a positive result.

Is there anything I can do to stop getting HPV?

Yes, the HPV vaccine can stop you getting HPV. The HPV vaccine normally consists of two jabs and is routinely offered to girls and boys aged 12 to 13 in secondary schools. If you missed out at school but are under 25 you can still have your jabs for free on the NHS through school or your GP surgery. It’s also available to pay for privately if you missed out.

The HPV vaccine is also available for men who have sex with men up to the age of 45 and some transgender people are eligible for the vaccine. Check out the NHS advice on eligibility here. It’s worth noting if you’re over 15 you’ll need three doses of the vaccine instead of two.

The vaccine doesn’t protect against all types of HPV, but is effective at protecting against some types, reducing cervical cell changes, and reducing the risk of some cancers including cervical cancer.

Condoms may also reduce your risk of HPV but do not completely protect against it. If you have HPV, just like trying to fight off any cold or virus, it’s recommended that you try to keep leading a healthy, balanced lifestyle, and quit smoking (a major risk factor for cervical cancer and a weakened immune system). This gives your immune system a better chance of clearing the virus.

Are there any symptoms I should look out for?

While HPV is symptomless for many people, if you receive a positive HPV result on your cervical screening test and are told to come back in a year, you may also be told to look out for bleeding after sex or between periods. There are many reasons you may experience irregular bleeding patterns, especially if you are using hormonal contraception, and it’s not likely to be cancer.

However if you are experiencing persistent bleeding after sex or between periods you should be examined by your GP, whether or not you’ve had a positive HPV result. It’s important to note there is a tiny proportion of cervical cancers that cannot be prevented through cervical screening and cervical screening is not for people with symptoms. If you are worried about symptoms, see your GP for an examination.

Our handy guide to spotting whilst on contraception and when to see a doctor about it will save you many a late night panic Google.

What is the process for cervical screening?

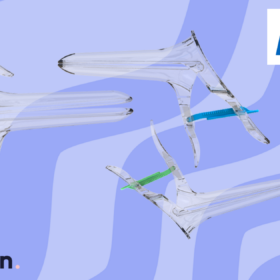

If you own a cervix in the UK you will be invited for a cervical screening (previously called a smear test). A routine cervical screening test usually takes 5-10 minutes, in which you undress from the waist down and lie on an examination bed. The nurse will gently insert a speculum into your vagina to open the cervix, and then take a sample of cells with a small brush.

The frequency of cervical screenings is based on your level of risk.

- If no HPV is found, you’ll be invited for screening in England every 3 years aged 25-49, or every 5 years if you’re aged 50-64. In Scotland and Wales, you’re invited for a screening every 5 years, whatever your age.

- If HPV is found, but you have no cell changes, you’re invited back in 1 year to check if the HPV has cleared. If you get this result 3 times in a row, you will be invited for a colposcopy.

- If HPV is found and you have cell changes, you will be invited for a colposcopy for further tests.

A colposcopy is a follow up to a cervical screening. The colposcopist will take a closer look at your cervix (so can you FYI, they put it on a screen) using a magnifying lens.They then put liquid solutions on the cervix which makes any abnormalities stand out. The colposcopist may take a small biopsy if they notice any changes.

If your cervical screening result comes back positive, or your colposcopy shows abnormal cell changes, don’t panic. Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust has excellent resources and support for those wanting more information after a positive result.

What is LLETZ?

Large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) is a type of surgery that removes a small part of the cervix using a thin wire loop with an electrical current. It can be used to treat abnormal cells or early stage cervical cancer, as well as for cervical cancer diagnosis.

Does HPV impact fertility or pregnancy?

HPV has no effect on fertility, whether you want to try for a baby, or if you are pregnant.

If you are pregnant and due to have cervical screening, you’ll usually be advised to wait for 12 weeks after giving birth as it can be more difficult to get clear results during pregnancy. Some women may be advised to have cervical screening at an antenatal appointment and if needed colposcopy can be done safely during pregnancy. When it comes to giving birth, vertical transmission (from mother to baby during vaginal delivery) of HPV is known to occur but the risk is low and babies usually clear the virus on their own.

When it comes to the effects that LLETZ treatment can have on childbirth, it is dependent on the type of treatment you received and the extent. Only about 2% of people who become pregnant after LLETZ will give birth prematurely. Giving birth prematurely is more likely if you have had LLETZ more than once or had more than 10mm of your cervix removed (which is not common in LLETZ treatment).

Is there any link between the pill and HPV?

Studies have consistently reported a small increased risk of cervical cancer associated with using the combined pill. This risk decreases with time after stopping. Among those with persistent HPV infection, use of the combined pill for more than 5 years may increase the risk of cervical cancer. Overall this risk is very low whether you’ve used the pill for a long time or not.

This risk is similar with the implant and injection, however, research hasn’t found any increased risk of cervical cancer associated with the progestogen only pill. Although more research needs to be done looking at HPV and contraception use, we do know that keeping up with cervical screening reduces the risk of cervical cancer.

It’s important to know that if you have an HPV positive result from your cervical screening you can happily continue your contraception including the combined pill, patch or ring. Cervical cancer is not driven by hormones. Therefore, in the case of someone diagnosed with cervical cancer, the benefits of combined hormonal contraception are still considered to outweigh the risks of unplanned pregnancy, so you are able to continue with this method.

Our medical review process

This article has been medically reviewed for factual and up to date information by a Lowdown doctor.