Contraception and cancer – what’s the risk?

This guide has been peer reviewed by the medical team at The Lowdown and the FSRH and is regularly reviewed as per both clinical content policies

In this article

What's the lowdown?

Most people who choose to use contraception do not expose themselves to long-term cancer harms and instead may benefit from a lowering of their risk of some cancers which persists for many years after stopping use⁵

Hormonal contraception can increase your chances of developing breast and cervical cancer, but these risks are small

Keeping up to date with cervical screening, getting the HPV vaccination if you’re eligible, and using condoms can help protect yourself against cervical cancer

Hormonal contraception has a protective effect against endometrial (womb), ovarian and bowel cancer

The copper coil could also have a protective effect against endometrial and cervical cancer.

It’s something nobody likes to think about, but cancer can’t be ignored, and it’s important that we’re clued up about our individual risks. Lots of people believe that particular types of contraception increase your risk of cancer, but that might not be entirely true. In fact, some contraceptives might actually protect you against certain types of cancer.

Let’s dive into different types of contraception and what impact these can have on your risk of developing some types of cancer.

Combined hormonal contraception

Breast cancer

Combined contraceptive methods contain both oestrogen and progestogen. The most common combined contraceptive method is the combined pill. Microgynon, Cilest and Yasmin are all popular brands of the combined contraceptive pill. The patch and the vaginal ring are also combined contraceptive methods.

We’ve known for some time that the combined pill slightly increases your risk of developing breast cancer. Breast cancer is rare in younger women who are users of contraception so the increase in risk with the combined pill is therefore very small. A 2023 study¹ found that for every 100,000 women who are aged 35-39, 265 more women who have been using oral contraceptives, so combined or progestogen-only pills, for 5 years could develop breast cancer in the next 10 to 15 years. The risk is smaller in younger women suggesting an extra 61 women per 100 000 aged 25 to 29 years old and an extra 8 women per 100,000 aged 16 to 25 years old will develop breast cancer.

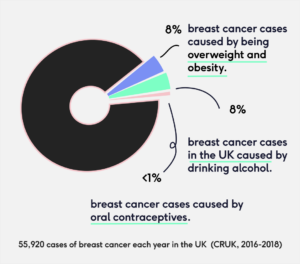

It’s important to point out that your risk of developing breast cancer is also dependent on factors other than your contraception. Whether or not you smoke, your weight and your genes all play a role. So let’s put this into perspective: there are almost 56,000 cases of breast cancer each year in the UK of which 8% are caused by obesity and being overweight and another 8% are caused by drinking alcohol. Less than 1% are caused by oral contraceptives.²

The slightly elevated risk of breast cancer reduces once you stop taking the pill, and ten years after stopping, your risk will be back to normal.¹

One study³ also found that the amounts and types of oestrogen and progestogen in your combined contraception can affect your risk of developing breast cancer, but there isn’t enough research to expand on this just yet.

Just a note… If you have a family history of breast cancer, or know that you have a faulty BRCA gene, you should speak to your doctor before beginning combined contraception. This is because you might already be at a higher risk of developing breast cancer. Everyone has BRCA genes, which protect us against breast and ovarian cancers. Some people have a faulty BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, meaning this protective effect doesn’t work as it should.

Ovarian cancer

Every time we ovulate, our ovaries are slightly damaged. Damage to the ovaries, over time, can cause ovarian cancer in some cases. When we take hormonal contraception, which stops ovulation and prevents this damage from occurring, this can reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer.

A huge study in Denmark⁴ which looked at nearly two million women over a nineteen year period found that any combined hormonal contraception – like the pill, ring and patch – provided a significant protective effect against ovarian cancer. This effect was more pronounced the longer a woman had been taking her contraception, and reduced once she stopped.

Other studies⁵ have found a benefit of decreased risk of ovarian cancer for many years after stopping hormonal contraception, and that this gradually reduces over time.

Endometrial Cancer

Endometrial cancer is cancer of the lining of the womb. Users of the combined pill have been found to have half the risk of developing endometrial cancer than those who have never used hormonal contraception, and this protective effect is the highest if you are currently taking combined contraception.⁵ People who recently stopped taking combined contraception still have a reduced risk, and this will slowly decrease the longer it is since stopping.

The protective effect against endometrial cancer has also been found across all combined contraception types,⁶ and it is thought that this protection could last up to twenty years after stopping contraception in some cases.

Bowel Cancer

A study followed 46,000 women to monitor the long term impact of taking the combined contraceptive pill.⁵ The study found that taking the pill for any length of time lowered the cases of bowel cancer.

Progestogen-only contraception

Breast cancer

Unlike combined contraceptive methods, progestogen-only contraception contains no oestrogen – just progestogen. The mini pill is a form of progestogen-only contraception, and brands like Micronor, Noriday and Cerazette are popular in the UK. The implant and the injection and the hormonal coil (aka hormonal IUD or IUS) are also forms of progestogen-only contraception.

A study published in 2023 looked at nearly 30,000 patient records held by GPs in the UK, including almost 10,000 women under 50 years old who had breast cancer diagnosed between 1996 to 2017.¹ The study revealed that similarly to the combined pill, current or recent users of progestogen-only contraceptives were found to be at slightly increased risk of breast cancer. There was no significant difference between the types of progestogen-only methods and their effects on breast cancer. We discuss this new study more in our article on progestogen-only contraception and breast cancer.

Currently, unlike combined methods, progestogen-only methods are generally considered safe for people with a BRCA gene mutation to use. Someone with current breast cancer, and most people with a history of breast cancer, should not use any form of hormonal contraception.⁷

Ovarian cancer

The Danish study didn’t find any protective effects of progestogen-only contraception, but there are others that have. Using the hormonal coil has been associated with reduced cases of ovarian cancer,⁸ as has the injection,⁹ both of which are progestogen-only methods.

It is possible that inconsistencies in the research for progestogen-only contraception are because of the way certain progestogen-only contraceptives work. While most hormonal contraception works to suppress ovulation on some level, some progestogen-only contraceptives do so more than others. It could be that those that suppress ovulation less (like the hormonal coil, which tends to prevent pregnancy by thinning the lining of the womb and thickening the cervical fluid at the neck of the womb) see less consistent protective effects in the research.

Endometrial cancer

Research into the effects of progestogen-only contraceptive methods on endometrial cancer risk is less common, but does suggest that these methods provide similar protection against the disease.⁶

Research that looked at all oral contraceptives and found a significant protective effect against endometrial cancer.¹⁰

The Mirena, Levosert and Benilexa brands of hormonal coil, are also licensed for use to protect the womb lining from the effects of oestrogen used in hormonal replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms.¹⁵ This is because if oestrogen is used to treat menopausal symptoms without progestogen, this will cause the womb lining to grow, risking cancerous changes.

People who have infrequent periods (less than every three months) because of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) can use contraceptive options such as the combined pill or hormonal coil (IUS) to keep the lining of the womb thin and reduce their risk of cancerous changes.

Bowel cancer

Researchers have looked at all oral contraceptives together rather than progestogen-only pill alone, but have found a significant protective effect against bowel cancer (a reduction of 14-19%).¹¹

Hormonal contraception and cervical cancer

There is evidence that long-term use of both the combined and mini pill can increase your risk of cervical cancer by up to four times.¹² This risk increases the longer you are taking your contraception, with people who have been using oral contraceptives for five years or more having the greatest risk.¹² ¹³

For around 10% of women in the UK who develop cervical cancer, this is linked to oral contraceptive use.¹³ This might sound alarming, but there is also evidence that this risk diminishes once you stop taking the pill, and to put it into perspective, less than 1% of UK women develop cervical cancer during their lifetime.¹³ This number includes those who are taking oral contraceptives and those who are not.

It’s difficult to say whether particular types of hormonal contraception, like the vaginal ring, injection, patch, hormonal coil and implant, have a lesser or greater effect on your risk of developing cervical cancer. More research is needed in this area.

It’s also important to remember that your risk of developing cervical cancer, whether you use the pill or not, is extremely low if you do not have human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is common, and usually goes away on its own and doesn’t cause any problems – most people won’t even know they have had it. Keeping up to date with your cervical screening, getting vaccinated against HPV if you are eligible, and using condoms are great ways to protect yourself from HPV and from any greater risk of cervical cancer that it may cause.

Non-hormonal methods

There is evidence that users of the copper coil have reduced rates of cervical cancer and reduced rates of endometrial cancer.¹⁴

This article can help you learn more about various contraception options, but it does not give medical advice. You should always speak to a nurse or doctor when making choices about contraception and before starting a new method.

Our medical review process

This article has been medically reviewed for factual and up to date information by a Lowdown doctor.